Will you help encourage and connect the church?

Give NowWill you help encourage and connect the church?

Give NowFor the hanged and beaten, for the shot, drowned, and burned. For the tortured, tormented, and terrorized. For those abandoned by the rule of law.

We will remember with hope because hopelessness is the enemy of justice. With courage because peace requires bravery. With persistence because justice is a constant struggle. With faith because we shall overcome.

So reads a placard in the middle of The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a monument remembering the lives of the hundreds of African Americans lost to lynching. Any visit to the tumultuous epicenter of the country’s civil rights movement that is Alabama holds this history of horror and hope in tension. In September, through a generous gift from a donor, 20 Christianity Today staff and leaders spent three days in Birmingham, Montgomery, and Selma. The following photos offer a glimpse of the cruel and triumphant history to which this group bore witness.

Text by Morgan Lee. Photos by Valerie Broucek.

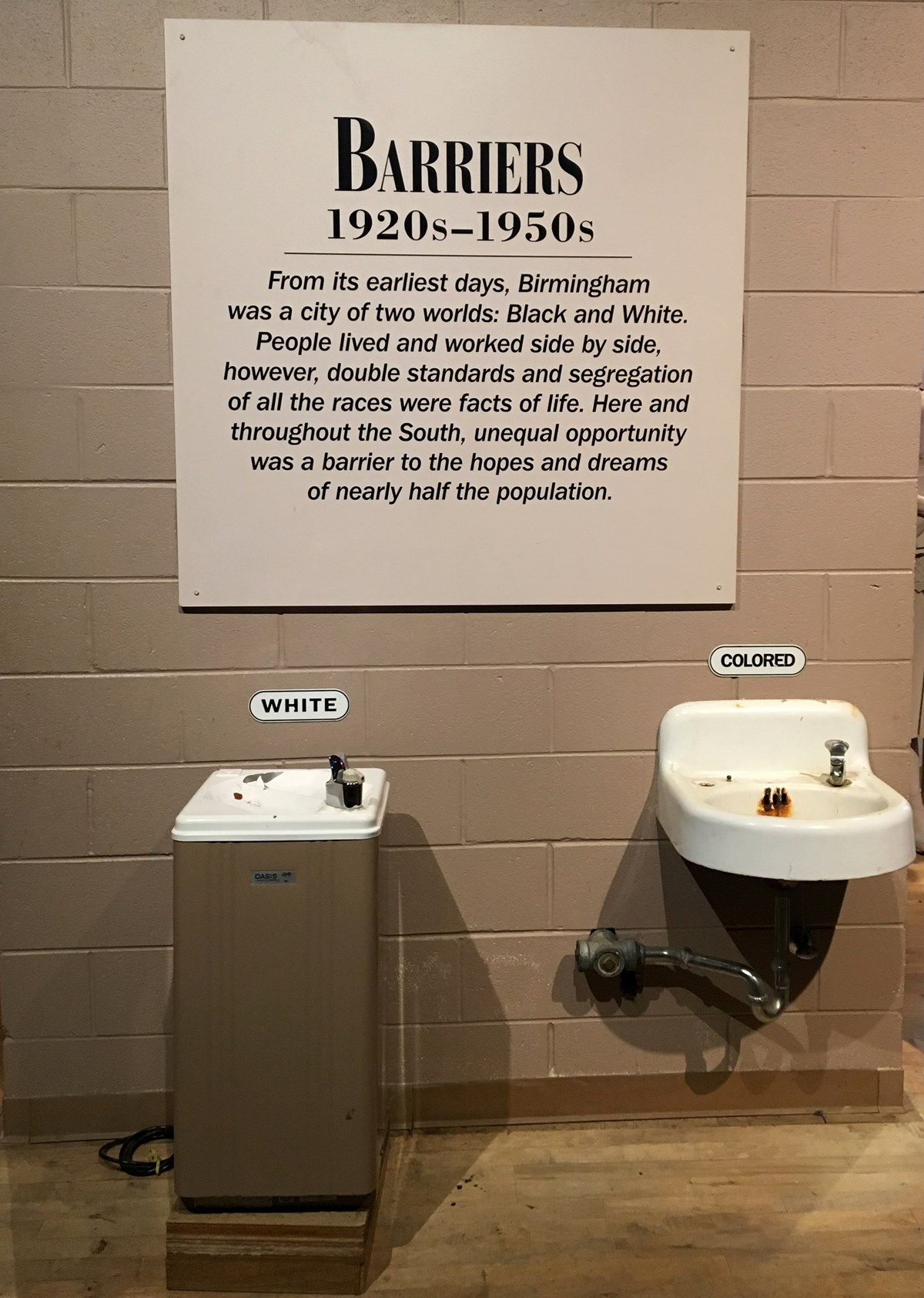

Despite being founded six years after the end of the Civil War, Birmingham nevertheless adopted the Jim Crow norms that defined much of the South.

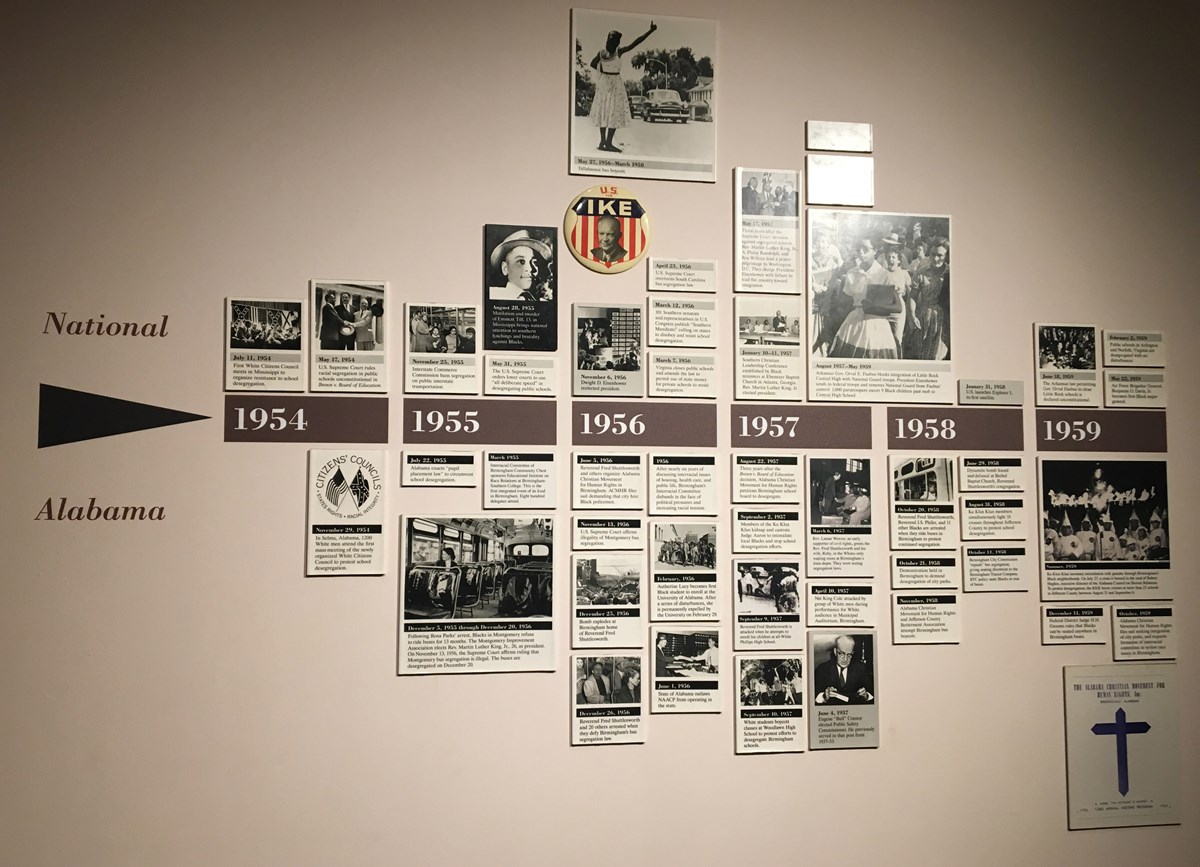

On the first day of the trip, the group visited the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute which told the story of the city since its inception through films, artifacts, and timelines.

“The various timelines in Birmingham’s Civil Rights Institute really captured my attention—and forced me to reflect on how many important events I had missed or hadn’t been a part of my education.

As one of the older members of the group, I can recall exactly where I was when both President Kennedy and his brother Bobby were assassinated, but I cannot begin to recall were I was when four African-American girls were killed at 16th Street Baptist Church or when Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated.

It has created a good deal of dissonance in my heart and soul. Honestly, I think that’s a good thing—especially if it ends up making me more sensitive and more aware of issues and stories related to race and discrimination.”

—Chris Lutes, planning and web editor, Church Law and Tax

In the afternoon, the group walked across the street to 16th Street Baptist Church. The spiritual home of the city’s black elite, the congregation initially struggled to fully get on board with the Civil Rights Movement. Soon after it changed its posture, a bomb exploded at the church on a Sunday morning, killing four little girls.

At the church, the group heard from a church member, who told a story about going behind his parents’ back to participate in the 1963 Children’s Crusade. During the two-day event, more than 1,000 children skipped school only to face the wrath of the commissioner of public safety, Bull Connor. After the first day, many of the children were arrested. After the second, Connor ordered police to spray the children with water hoses, hit them with batons, and threaten them with dogs. For his part, the church member, who made it home safely, never told his late mother and only recently disclosed the information to his father.

In 2018, the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration opened to the public. Through traditional and innovative multimedia storytelling techniques, the institution connects the history of slavery in America to current mass incarceration injustices. Guests can make eye contact with previously incarcerated people telling their stories over video, watch reels of the family members of victims of lynching grieve their ancestors’ deaths, and read the advertisements describing enslaved people set to be auctioned.

Located in Montgomery, on the site of a former warehouse where enslaved black people were imprisoned, Alabama’s capital was a central slave market hub. According to Equal Justice Initiative, “Montgomery's proximity to the fertile Black Belt region, where slave-owners amassed large enslaved populations to work the rich soil, elevated Montgomery's prominence in domestic trafficking, and by 1860, Montgomery was the capital of the domestic slave trade in Alabama, one of the two largest slave-owning states in America.”

No photos were allowed inside the museum.

“One thing that had a profound impact on me were the letters written by inmates in The Legacy Museum. There were probably about 15 letters from people in prison to EJI founder Bryan Stevenson asking him to help them or people they knew. They were heartbreaking and hard to read, but I made myself read every single one of them because I wanted to respect the lives behind the letters. I wanted to respect the children who had lost their childhoods. I wanted to respect the families who had lost their mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, daughters, and sons. I wanted to respect the honesty and repentance behind the words. But most of all I wanted to respect the image of God in each person who wrote a letter. The person who God created and loves deeply.

My heart breaks for these people. My heart breaks for the people who did nothing, who were wrongly accused, but are spending time in prison for something they didn’t do. My heart breaks for the children who made a mistake, but because of the color of their skin and the economic situations of their parents their childhood was taken away instead of giving them a second chance. My heart breaks for the adults who were given sentences far beyond what someone who looks like me would receive, who are living without their families, who are slipping away from hope with each day.”

—Caitlin Edwards, marketing and communications strategist

A ten-minute shuttle ride from the museum through downtown Montgomery took the group to The National Memorial for Peace and Justice. Through 800 steel columns marking the counties and the names of those who perished by lynching in that locale, it remembers the more than 4,000 African American men, women, and children hunted down and murdered. (This number is only the number of lynchings that EJI has been able to document.)

Christianity Today's trip came two years after the September 2017 cover story, “Facing Our Legacy of Lynching,” which discussed EJI’s then-proposed museum and memorial and wrestled with the white evangelical church’s response (or lack thereof) to these atrocities.

“As we went from Birmingham to Montgomery to Selma, I felt more weight as I considered our nation’s sins against our African American sisters and brothers—and the clear ties from slavery to lynching and segregation, and now our broken criminal justice system and mass incarceration. As a group, it was important that we lamented these systematic injustices in our country, but also important to acknowledge and repent of the church’s role in it and its silence. I kept thanking the Lord and feeling so humbled for the opportunity to experience and work through this with colleagues who are considering and praying about how we can make some of these wrongs right.”

—Cory Whitehead, executive director of mission advancement

Martin Luther King Jr. began his first full-time pastorship at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama in 1954. Inside Dexter’s basement, King helped organize the bus boycott sparked by Rosa Park’s decision not to move to the back of the bus. King served here until 1960.

While King was a pastor at Dexter Avenue, the church’s parsonage where he lived with his family was bombed in 1956 by white segregationists.

This plaque commemorates the 1965 voting rights march from Selma, with the capitol building in the background. A similar size plaque directly on opposite remembers Confederate president Jefferson Davis’s inauguration parade.

In the middle of downtown Montgomery sits this fountain, the site of many of Montgomery’s barbaric slave auctions.

“Our last day we went to Selma and walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. We learned about the march from Selma to Montgomery, and I was struck by the courage and the tenacity of the marchers. Even though they were literally beaten back from their first attempt, this was a people that persevered against brutality with peace and love. That left me thinking about what is our (metaphorical) bridge today, and how can I muster the bravery to march across.”

—Sarah Gordon, art director, Christianity Today

In anticipation of the trip, the group read and discussed EJI founder Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy. In his memoir, Stevenson writes about his work advocating for men and women he believes have unjustly been sentenced to death row and calls for urgency around building systems that work justly and equitably for poor black people.

Over the course of the trip, the group also spent time communally reflecting and debriefing the stories, experiences, and history they heard and absorbed.

The group at 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama.

To learn more, EJI has produced this short film on slavery to incarceration and a behind-the-scenes look at the lynching memorial. More information on Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy can be found here.